Measuring the Cost of Cybercrime

tl;dr (too long; didn't read)

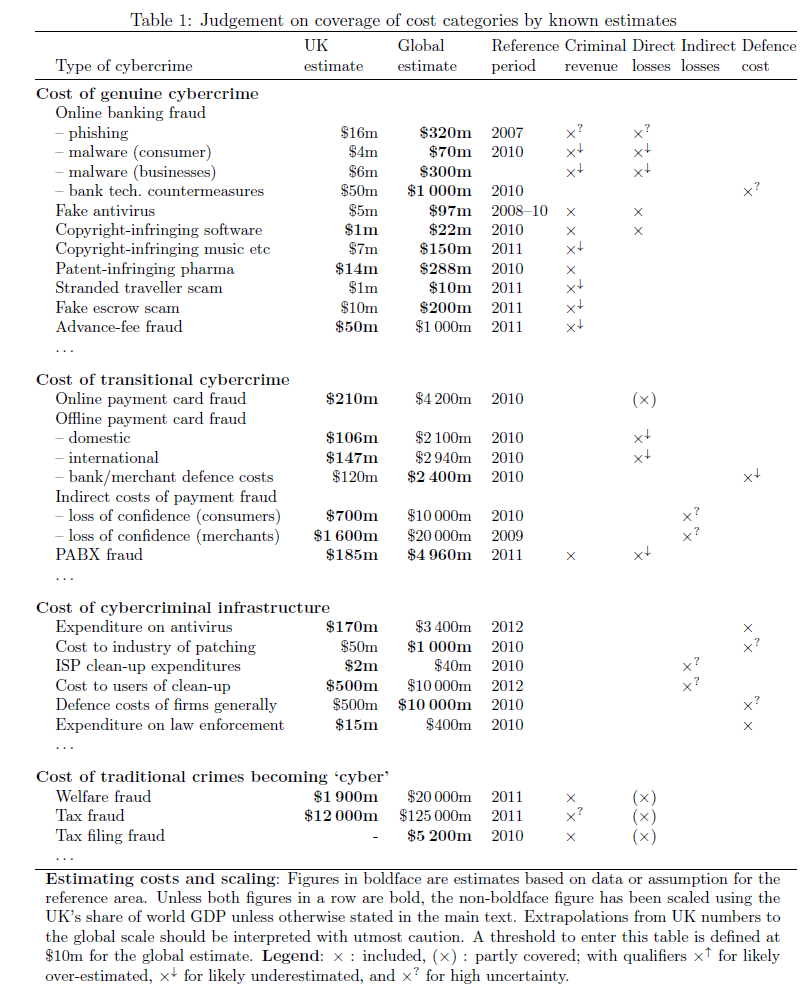

The authors attempt to calculate the approximate cost to individuals and society of several types of cybercrime.

Direct losses: losses, damage, or other suffering felt by the victim as a consequence of a cybercrime.

Indirect losses: the losses and opportunity costs imposed on society by the fact that a certain cybercrime is carried out, no matter whether successful or not and independent of a specific instance of that cybercrime. Indirect costs generally cannot be attributed to individual victims.

Defence costs: prevention efforts, including direct defence costs, i.e., the cost of development, deployment, and maintenance of prevention measures, as well as indirect defence costs, such as inconvenience and opportunity costs caused by the prevention measures.

Cost to society: direct losses + indirect losses + defence costs

Criminal revenue is in practice significantly lower than direct losses and much lower than direct plus indirect losses.

- Traditional frauds such as tax and welfare fraud cost each of us a few hundred pounds/euros/dollars a year. The costs of defences, and of subsequent enforcement, are much less than the amounts stolen.

- Transitional frauds such as payment card fraud cost citizens a few tens of pounds/euros/dollars a year. Online payment card fraud typically runs at 0.3% of the turnover of e-commerce firms. Defence costs are broadly comparable with actual losses, but the indirect costs of business foregone because of the fear of fraud, both by consumers and by merchants, are several times higher.

- The new cyber-frauds such as fake antivirus net their perpetrators relatively small sums, with common scams pulling in tens of cents/pence per year per head of population. In total, cyber-crooks' earnings might amount to a couple of dollars per citizen per year. But the indirect costs and defence costs are very substantial -- at least ten times that. The clean-up costs faced by users (whether personal or corporate) are the largest single component; owners of infected PCs may have to spend hundreds of dollars, while the average cost to each of us as citizens runs in the low tens of dollars per year. The costs of antivirus (to both individuals and businesses) and the cost of patching (mostly to businesses) are also significant at a few dollars a year each.

Conclusion: We should spend less in anticipation of computer crime (on antivirus, firewalls etc.) and an awful lot more on catching and punishing the perpetrators.

Abstract

In this paper we present what we believe to be the first systematic study of the costs of cybercrime. It was prepared in response to a request from the UK Ministry of Defence following scepticism that previous studies had hyped the problem. For each of the main categories of cybercrime we set out what is and is not known of the direct costs, indirect costs and defence costs -- both to the UK and to the world as a whole. We distinguish carefully between traditional crimes that are now `cyber' because they are conducted online (such as tax and welfare fraud); transitional crimes whose modus operandi has changed substantially as a result of the move online (such as credit card fraud); new crimes that owe their existence to the Internet; and what we might call platform crimes such as the provision of botnets which facilitate other crimes rather than being used to extract money from victims directly. As far as direct costs are concerned, we find that traditional offences such as tax and welfare fraud cost the typical citizen in the low hundreds of pounds/Euros/dollars a year; transitional frauds cost a few pounds/Euros/dollars; while the new computer crimes cost in the tens of pence/cents. However, the indirect costs and defence costs are much higher for transitional and new crimes. For the former they may be roughly comparable to what the criminals earn, while for the latter they may be an order of magnitude more. As a striking example, the botnet behind a third of the spam sent in 2010 earned its owners around US$2.7m, while worldwide expenditures on spam prevention probably exceeded a billion dollars. We are extremely inefficient at fighting cybercrime; or to put it another way, cyber-crooks are like terrorists or metal thieves in that their activities impose disproportionate costs on society. Some of the reasons for this are well-known: cybercrimes are global and have strong externalities, while traditional crimes such as burglary and car theft are local, and the associated equilibria have emerged after many years of optimisation. As for the more direct question of what should be done, our figures suggest that we should spend less in anticipation of cybercrime (on antivirus, firewalls, etc.) and more in response -- that is, on the prosaic business of hunting down cyber-criminals and throwing them in jail.

Review

Pros

I thought the paper presented an interesting and thoughtful way to break down the types of cybercrime costs (direct, indirect, etc).

The authors also did a great job surveying and aggregating different types of cyber crimes and their associated costs.

Cons

Many of the costs are heavily estimations and may easily be off up to an order of magnitude, which the authors readily admit. This is understandable, as it's difficult to get precise numbers.

There was limited novelty of technique / methodology, they primarily reference and aggregate existing work. To be fair, the latter is the intention of the paper.

Notes

Choose to estimate global figures, as sometimes there is only global or only UK data. They scale UK-only data based on that it's roughly 5% of world GDP.

Criminal revenue: the monetary equivalent of the gross receipts from a crime, excluding any `lawful' business expenses of the criminal. (e.g. paying for hosting services)

Examples of Losses

Direct losses:

- money withdrawn from victim accounts

- time and effort to reset account credentials (for both banks and consumers)

- distress suffered by victims

- secondary costs of overdrawn accounts: deferred purchases, inconvenience of not having access to money when needed

- lost attention and bandwidth caused by spam messages, even if they are not reacted to

Indirect losses:

- loss of trust in online banking, leading to reduced revenues from electronic transaction fees, and higher costs for maintaining branch staff and cheque clearing facilities

- missed business opportunity for banks to communicate with their customers by email

- reduced uptake by citizens of electronic services as a result of lessened trust in online transactions

- efforts to clean-up PCs infected with the malware for a spam sending botnet

Defence costs:

- security products such as spam filters, antivirus, and browser extensions to protect users

- security services provided to individuals, such as training and awareness measures

- security services provided to industry, such as website ‘take-down’ services

- fraud detection, tracking, and recuperation efforts

- law enforcement

- the inconvenience of missing an important message falsely classified as spam

Defence costs, like indirect losses, are largely independent of individual victims. Often it is even difficult to allocate them to individual types of cybercrime. Defences can target the actual crimes or their supporting infrastructure, and the costs can be incurred in anticipation of or reaction to crimes, the latter being to deter copycats.

It is possible to spend too much on defense -- 9/11 terrorist attacks costed $500,000 to carry out and by 2008 U.S. had spent over $3 trillion on defense costs and wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The misallocation of resources associated with cybercrime results mostly from economic and political factors rather than from behavioural ones. Globalisation means that for much online crime, the perpetrators and victims are in different jurisdictions. This reduces both the motivation and the opportunity for police action.

Types of Fraud Considered

- Online payment card fraud - may get charged back to the merchant, the bank, or bounched back to the owner.

- Online banking fraud - user banking credentials obtained via phishing or keyloggers

- In-person payment card fraud - commonly attackers use tampered PED terminals or ATM skimmers to capture card data and make forged cards that operate in fall-back mag-stripe mode.

- Fake antivirus - a pop-up on a website warns the user that their computer is infected with malware, the link cause fake antivirus to be downloaded and run.

- Infringing pharmaceuticals - direct costs: risk of fraud or health risks. indirect: spam compaigns.

- Copyright-infringing software - societal costs: lost licensing revenues to copyright and brand holders. 20% of one survey responded that they had purchased software advertised in spam email.

- Copyright-infringing music and video - "Job losses among music company middle managers are just the creative destruction inherent in technological progress."

- 'Stranded traveller' scams - compromised email account emails friends, "I'm stuck in [place] and was mugged, need money to leave."

- 'Fake escrow' scams - victim believes they won an online auction for a car/motorbike. Seller proposes using a third-party escrow for the transaction, car is never delivered.

- Advanced fee fraud - aka as the Nigerian prince. Pay a little money up front to get a huge payback.

- PABX fraud - fraud losses from telephony, fixed and mobile. PABX: criminals reconfigure company's telephone system to accept incoming calls and relay them onward. They then sell phone cards that use it.

- Industrial cyber-espionage and extortion - there is no reliable evidence of the extent or cost of industrial cyber-espionage and extortion, we do not include any figures for these crimes in our estimates.

- Fiscal fraud - tax and welfare fraud committed against the government. Criminals in the USA have been impersonating citizens by electronically filing fraudulent tax returns using stolen lists of names and Social Security numbers.

- Other commercial fraud - insider trading, embezzlement, control fraud (executives loot their company). Not considered in this paper because they involve the exercise of power in interpersonal and institutional relationships rather than claims made through an automated system.

The Infrastructure Supporting Cybercrime

While these activities are often referred to directly as cybercrime, they enable many different crimes. They estimate the infrastructure's cost separately to avoid double counting.

Botnets - Herley and Florencio estimated an upper bound to botnet herders' income of 50c per machien per annum.

It is very difficult to estimate the size of botnets. Previous approaches have relied on counting number of unique IPs associated with botnet activity. However, dynamic IP address allocation can cause the same machine to show up as many IP addresses, causing the number of believed bots to be off by an order of magnitude.

- Botnet mitigation by consumers - manual updates, behind the scenes updates by software vendors.

- Botnet mitigation by industry - ISPs and hosting providers who act against infected machines on their networks, antivirus companies.

- Other botnet mitigation costs - malware may drive users to a given more locked down platform, antivirus adoption, software vendors patching products, law enforcement.

Pay-per-install - malware authors pay a PPI operator to install their malware on X PCs in a geographic area for a fee.

Final Thoughts

Traditional acquisitive crimes, such as burglary and car theft, tend to have two properties. The first is that the impact on the victim is greater in financial terms than either the costs borne in anticipation of crime, or the response costs afterwards such as the police and the prisons.

Drilling down further into the victim costs, we find that for nonviolent crimes the value of the property stolen or damaged is much greater than the cost of lost output, victim services or emotional impact.

The criminal justice system recognises the quite disproportionate social costs of robbery as opposed to burglary. While robbers get longer sentences than burglars do, cyber-crooks get shorter ones. This is probably because cyber-crimes, being impersonal, evoke less resentment and vindictiveness. Indeed, the crooks are simply being rational: while terrorists try to be annoying as possible, fraudsters are quite the opposite and try to minimise the probability that they will be the targets of effective enforcement action.

Why does cyber-crime carry such high indirect and defence costs? Many of the reasons have been explored in the security-economics literature: there are externalities, asymmetric information, and agency effects galore. Globalisation undermines the incentives facing local police forces, while banks, merchants and service providers engage in liability shell games. We are also starting to understand the behavioural aspects: terrorist crimes are hyper-salient because the perpetrators go out of their way to be as annoying as possible, while most online crooks go out of their way to be invisible.

Diagrams

The following are relevant diagrams from the paper. Several diagrams and performance graphs have been omitted, see the paper

for details.

blog comments powered by Disqus